1.800.221.5175

Mathematics

Sadlier PreK with Wiley Blevins

Knowledge-Building Early Childhood Program

Preview

|

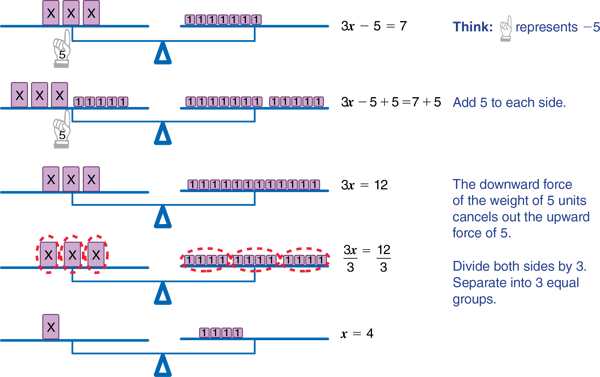

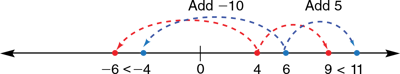

Progress Mathematics

Grades K–8

Reading & Writing

From Phonics to Reading

Grades K–3

Building Reading Success with Wiley Blevins

Grades K–5

Vocabulary

Vocabulary Workshop, Tools for Comprehension

Grades 1–5

Vocabulary Workshop Achieve

Grades 6–12+

|